|

| |

Chinese- Perfect Strangers of the Eastern Sea

Vu Huu San

Chinese are Purely Land Men

Ricci and his fellow priest, Michele Ruggieri, stayed for seven years

in Chao-ch'ing, a town west of Canton. They built a mission house, and despite popular

suspicion and occasional hails of rocks from the hostile populace, they were accepted as

men of learning. On the wall of the mission's reception room Ricci mounted his map of the

world. As Ricci himself reported:

Of all the great nations, the Chinese have had the least commerce,

indeed, one might say that they have had practically no contact whatever, with outside

nations, and consequently they are grossly ignorant of what the world in general is like.

True, they had charts somewhat similar to this one, that were supposed to represent the

whole world, but their universe was limited to their own fifteen provinces, and in the sea

painted around it they had placed a few islands to which they gave the names of different

kingdoms they had heard of. All of these islands put together would not be as large as the

smallest of the Chinese provinces. With such a limited knowledge, it is evident why they

boasted of their kingdom as being the whole world, and why they call it Thienhia, meaning,

everything under the heavens. When they learned that China was only a part of the great

east, they considered such an idea, so unlike their own, to be something utterly

impossible, and they wanted to be able to read about it, in order to form a better

judgment....

Ricci also gave some notes about the Chinese nature as following:

We must mention here another discovery which helped to win the good

will of the Chinese. To them the heavens are round but the earth is flat and square, and

they firmly believe that their empire is right in the middle of it. They do not like the

idea of our geographies pushing their China into one corner of the Orient. They could not

comprehend the demonstrations proving that the earth is a globe, made up of land and

water, and that a globe of its nature has neither beginning nor end. The geographer was

therefore obliged to change his design and, by omitting the first meridian of the

Fortunate Islands, he left a margin on either side of the map, making the Kingdom of China

to appear right in the center. This was more in keeping with their ideas and it gave them

a great deal of pleasure and satisfaction. Really, at that time and in the particular

circumstances, one could not have hit upon a discovery more appropriate for disposing this

people for the reception of the faith....

Because of their ignorance of the size of the earth and the exaggerated

opinion they have of themselves, the Chinese are of the opinion that only China among the

nations is deserving of admiration. Relative to the grandeur of empire, of public

administration and of reputation for learning, they look upon all other people not only as

barbarous but as unreasoning animals. To them there is no other place on earth that can

boast of a king, of a dynasty, or of culture. The more their pride is inflated by this

ignorance, the more humiliated they become when the truth is revealed.(See "The

Discoverers", Daniel J. Boorstin, Random House, New York, 1983, pp. 56-64)

Another Western scholar, James Fairgrieve, in his books "Geography

and World Power" (London, 1921), 242, has written: "China has never been a

sea-power because nothing has ever induced her people to be otherwise than landmen, and

landmen dependent on agriculture with the same habit and ways of thinking drilled into

them through forty centuries."

In a recent work, we find this statement in a very fine book: "Essentially

a land people, the Chinese cannot be considered as having possessed sea-power.... The

attention of the Chinese through the centuries have been turned inward towards Central

Asia rather than outward, and their knowledge of the seas which washed their coast was

extremely small." (F. B. Eldridge, The Background of Eastern Sea Power; Melbourne,

1948, 47.)

There are many reasons that The Chinese did not develop as a seafaring

nation. (since 2634 B.C.) The main reason was that the vast land-mass of China absorbed

their energies. Equally, the absence of neighbouring nations with whom to trade played a

large part in the development of the introspective conservatism of the Chinese. However,

Taiwan (Formosa) was noted for its fishing and an active local trade existed with the

mainland.

In the legends of China, chronicled in the Shu Ching (Canon of

History), the first three emperors, Fu Hsi, Shen Nung and Huang Ti, are each credited with

a share in the invention of all the main activities of the people, including matrimony,

building houses and the introduction of a calendar, but no mention is made of the sea,

ships or of fishing (although hunting is mentioned). It is against this background that

the virtual absence of Chinese sea-legend and sea sagas has to be viewed. (See Duncan

Haws and Alex A.Hurst, "The Maritime History of the World, -A Chronological Survey of

Maritime Events From 5,000 B.C. until the Present Day, Supplemented by Commentaries",

Teredo Books Ltd., Brighton Sussex, 1985.)

In the Introduction Chapter of "The Nanhai Trade", Wang

Gungwu also writes: The Chinese civilisation rose from the land, from the Huang Ho

Plain far from the mouth of the river. When it rose, its world consisted of the fields in

which the people tilled and for which they often fought, the rivers they feared and tried

to control and the towns and fortresses where they hid from their enemies. The sea was

only known as a peaceful boundary to the east that yielded salt and fish and as a deep and

limitless boundary that divided prince, sage and common man from the saints and immortals.

(See "The Nanhai Trade", Kuala Lumpur, 1959, page 3.)

Scholar Pin Ti Ho, who found out the backwardness in the Chinese

ability to adapt with the water environment, have clearly identified that: "...It

is sufficiently clear, therefore, that the rise of agriculture and civilization bore no

direct relation whatever to the flood plain of the Yellow River, and that, of all the

ancient peoples who developed higher civilizations in the Old and the New Worlds, the

Chinese were the last to know irrigation." (See Pin Ti Ho, "The Cradle of

the East", Chicago Press, 1975, page 48.)

Vietnamese are Naturally Seamen and Indigenous of the Easter Sea

On the contrary with the Chinese nature, Vietnamese have always been the experts in

the arts of naval warfare and maritime transportation since the very ancient time.

The Han Chinese wrote of southerners Viet people as follows "The Yủeh people by

nature a indolent and undisciplined. They travel to remote places by water and use boats

as we use carts and oars as we use horses. When they come (north - to attack) they float

along and when they leave (withdraw) they are hard to follow. They enjoy fighting and are

not afraid to die." (See "Eighth Voyage of the Dragon", Bruce Swanson,

Naval Institute Press, Annapolis 1982, page 11-12).

The vessels of the Yủeh in the Warring States period, however, were not all naval, and

we can be sure that there were trading expeditions at least along the coasts of Siberia,

Korea and Indochina. There were also some explorations of the Pacific itself. And of

course, as ever, inland water transport. (See Needham, Joseph; Wang Ling and Lu

Gwei-Djen, "Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4: Physics and Physical

Technology, part III: Civil Engineering and Nautics" Cambridge University Press:

Cambridge, 1971, page 441.)

The off-shore ships of the Tonking (North Vietnam) Area were

surprisingly big and so technically advanced for the Chinese observations. A 3rd-century

text of capital importance does so, however. It occurs in the Nan Chou I Wu Chih (Strange

Things of the South), written by Wan Chen, and run as follows:

The people of foreign parts (wai yu jen) call chhuan (ships) po. The

large ones are more than 20 chang in length (up to 150 ft.), and stand out of the water 2

or 3 chang (about 15 to 23 ft.). At a distance they look like 'flying galleries'

(ko tao) and they can carry from 600 to 700 persons, with 10,000 bushels (hu) of cargo.

The people beyond the barriers (wai chiao jen), according to the sizes

of their ships, sometimes rig (as many as) four sails, which they carry in a row from bow

to stern. From the leaves of the lu-thou tree, which have the shape of 'yung', and are

more 1 chang (about 7.5 ft.) long, they weave the sails.

The four sails do not face directly forwards. but are set obliquely,

and so arranged that they can all be fixed in the same direction, to receive the wind and

to spill it (Chhi ssu fan pu cheng chhien hsiang, chieh shih hsieh i hsiang chu, i

chhufeng chhui feng ). Those (sails which are) behind (the most windward one) (receiving

the) pressure (of the wind), throw it from one to the other, so that they all profit from

its force (Hou che chi erh hsiang she, i ping te feng li). If it is violent, they (the

sailors) diminish or augment (the sails) to receive from one another the breath of the

wind, obviates the anxiety attendant upon having high masts. Thus (these ships) sail

without avoiding strong winds and dashing waves, by the aid of which they can make great

speed."

This indeed a striking passage. It establishes without any doubt that in

the +3rd century southerners, whether Cantonese or Annamese, were using four-masted ships

with matting sails in a fore-and-aft rig of some kind. The Indonesian canted

square-sail is not absolutely excluded, but it would be unwieldy on a vessel with several

masts, and some kind of tall balanced lug-sail seem much more probable. (See Needham,

Joseph, Wang Ling and Lu Gwei-Djen, "Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 4:

Physics and Physical Technology, part III: Civil Engineering and Nautics" Cambridge

University Press: Cambridge, 1971, Page 600-601.)

Viet Nam is a maritime country. None of the plains on which the great

bulk of the population is concentrated lies very far from the coast.

"The sea therefore is constantly present in Vietnamese life. Its

products, salt and fish, play a vital role in the diet. The legendary emperors who founded

the Vietnamese monarchy are said to have had their thighs tattooed with sea monsters in

order to ensure a victorious return from their fishing expeditions. In the seventeenth and

eighteenth centuries English agents sent to Viet Nam by the East India Company

acknowledged that the Vietnamese were the best sailors in the Far East. Even more than the

often narrow coastal corridor of Central Viet Nam, the sea represents the main line of

communication between north and south- it is therefore an essential element of Vietnamese

National unity in the economic sphere." (Jean Chesneaux "The Vietnamese

Nation - Contribution To A History, Translated by Malcolm Salmon, Current Book

Distributors Pty. Ltd. Sydney, 1966)

Western merchants also testified to the hospitality of the Vietnamese.

By the old tradition of the sailors, they have especially expressed the genuine kindness

towards other mariners, as described in a memo on trade with this region written probably

between 1690 and 1700:

When a vessel is shipwrecked, it get a better welcome (in Cochinchina)

than anywhere else.. Ships come out from shore to salvage the equipment; nets are used to

recover merchandise which has fallen overboard. In fact, no effort is spared to put the

ship back into good condition. (See Taboulet, "La geste franẫaise en

Indochine." Paris, 1955, Vol. 1, p. 87.)

Like his fellow Jesuits Ricci and de Nobili in China and India, de

Rhodes never looked on the oriental Vietnamese as "underdeveloped" or even as

just plain hungry, benightedly awaiting the benefits of Western technocracy and superior

social structures. (See Rhodes Of Vietnam, The Travels and Missions of Father Alexander de

Rhodes in China and Other Kingdoms of the Orient, Translated by Solange Hertz, The Newman

Press - Westminster, Maryland, 1966.)

Two years before the "Mayflower" put ashore at Massachusetts,

a Portuguese Jesuit priest, Cristoforo Borri (the same Father Borri, have mentioned

above), landed with brother missionaries in Faifo, a Vietnamese port located near the

present city of Danang in Central Vietnam. (The Portuguese called all of Vietnam below the

18th parallel Cochinchina; they called the people Cochinchinese, to distinguish them from

the Chinese of China proper.)

Father Borri came as a friend and was so received by Vietnamese. This

delightful mathematician expressed great enthusiasm for the local inhabitants, even

commenting on the women’s feminine charms! Extolling their attire, he wrote that

"though decent, it is so becoming that one believes one is witnessing a gracious

flowering springtime." (See Georges Taboulet, "La geste Franẫaise en

Indochine," Paris, 1955, p. 59.)

The record he left compares the people with those of China, where

his journeys for the faith had also taken him. To his evident delight, he found the

Cochinchinese truly hospitable and "superior to the Chinese in their wit and

courage" (See Helen B. Lamb, "Vietnam’s Will to Live - Resistance to

Foreign Aggression from Early Times Through the Nineteenth Century", Monthly

Review Press, New York and London, 1972.)

The "South China Sea" has never been Chinese.

The Vietnamese Eastern Sea (Chinese South China Sea) probably did not

enter the Chinese geographical lexicon any earlier than the Han dynasty with the

absorption of southern China. During that era, Ma Yuan led a fleet of approximately 2,000

vessels to carry out the conquest of Northern Vietnam. As a result of this successful

military venture, the South China Sea might become an area of interest to Chinese

historians and geographers, but they made no specific references to its islands and

atolls - since then - for several centuries.

Though recent announcement of Chinese archaeological findings in the

Paracel Islands confirm some contact with the islands as early as the Wang Mang

interregnum, there is no proof that such contact was exclusively Chinese. On the contrary,

the sea route connecting T'ien-chu (India) and Fu-nan (Cambodia) with Canton (known as

Nan-hai chun or commandary of the Southern Sea) was well established by the first century,

but was dominated by non-Chinese seamen for many centuries thereafter. Even as the

importance of the Southern Sea trade grew in the third and fourth centuries, there is not

any textual evidence to suggest any official Chinese cognizance of the island atolls.

Indeed, not even the otherwise well chronicled voyages of the monks Fa Hsien and I Ching,

offers indirect, let alone unequivocal mention of the islands of the South China

Sea". (See Jon M. Van Dyke & Dale L. Bennett, "Islands and the Delimitation

of Ocean Space in the South China" Yearbook 1993, The University of Chicago.

Fa Hsien was surely a traveling Buddhist Monk. Like any other Chinese

at that time, they all rode non-Chinese ship as the common passengers.

Chinese shipping on the South China coast was usually insignificant;

and the passage makes it clear that some 'transfer'' must have taken place. The fact is

that the chief ships sailing along the China coast were those of the Yủeh. Since the

majority of the people of the southern coasts were not "sinicized" till much

later one, in some cases not until the T'ang dynasty (618-907) would be wrong to call the

Yủeh sailors and shipbuilders of this early period "Chinese" just because their

territories were under Chinese rule. Theirs could well have been the ships which first

took the imperial agents out to some Nanhai mart where a transfer was made to

''barbarian'' vessels for the rest of the journey. But as the Yủehs had now become the

subjects of the Han empire (-206 to 219), the author of the passage might have thought of

them as Chinese. In this text, however, it is still necessary to make the distinction

between the Yủehs and the Chinese... (See "Nanhai trade," Wang Gungwu, Kuala

Lumpur, 1959, page 23.)

South Sea, the places so stranger and so far-away with the Chinese

Since the third century B.C., when Chinese armies invaded the

South, the settlers from the north first came to the region, they occupied the land and

displaced the indigenous Yueh peoples. Slowly and steady migrations of Chinese had made

their way to the water world.

But, because their high plateau originality, the Chinese did not know

much about the vast sea located right next to their southern borders until very recently.

The Viet bronze vessels were described so vaguely in Chinese books and even the river

water in the Nam Nam Areas was completely out of the natural matter!

Attention was drawn by Julien (Stanislas, Notes sur l'Emploi Militaire

de Cerfs-Volants, et sur les Bateaux et Vaisseaux en Fer et en Cuivre, Tire'e

des Livres Chinois, Comptes Rendus hebdomadaires de l'Acad. des Sciences, Paris, 1847, no.

21, p. 1070.) to the fact that Chinese writings of the early + 4th century refer to the

covering of junk bottoms with copper. Thus the Shih I Chi, by Wang Chia, referring

to an embassy from the Jan-Chhiu I kingdom in the legendary reign of Chheng Wang, says: a

'Floating on the seething seas, the ambassadors came on a boat which had copper (or bronze

plates) attached to its bottom, so that the crocodiles and dragons could not come near

it.' (Among the Chinese texts which mention boats of bronze or copper are the Lin-I

Chi, Shui Ching Chu, Nan Yủeh Chih, Thai-Phing Huan Yủ Chi, Fang Yủ Chi, and

the Yuan-Ho Chủn Hsien Thu Chih (+814.)

It has now been shown that stories of metal boats occur abundantly in

the early Chinese literature of folklore and legend. They are particularly common in South

China and Annam, where they often form part of the epic exploits of the Han general, Ma

Yủan, who restored the far south to Chinese allegiance in the campaign of + 42 to + 44.

The bronze or copper boats of which people see the vestiges are thus associated with the

setting up of bronze columns to mark the southern limits of the empire, the casting of

bronze oxen as landmarks, and the building of canals to shorten sea voyages or make them

more safe. (See Hou Han Shu, also in the late +7th-century encyclopaedia Chhu

Hsủeh Chi, and Thai-Phing Huan Yủ Chi.)

The evidential texts date from all periods between the + 3rd and the +

9th centuries, but the only one which specifically mentions the bottom of a ship is the

early + 4th century Shih I Chi. Although it is quite possible, as

sinologists tend to think, that the idea of using metal in the construction of boats

was purely magical and imaginary in origin, it is at any rate equally possible that

some southern group of shipwrights in those ages had the services of smiths who beat metal

into plates fit for nailing to the hulls of their craft to protect the timbers … But

iron armour for (Viet) warships was no legend, as we shall see … (See Needham,

Joseph; Wang Ling and Lu Gwei-Djen, "Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4:

Physics and Physical Technology, part III: Civil Engineering and Nautics" Cambridge

University Press: Cambridge, 1971, page 665.)

Further more, in one of Chinese tall stories about the south; the early

+6th-century Shu I Chi describes a river in Tshang-chou the water of which is so dense

that metal and stone will not sink in it - the opposite of the 'weak water' - , and

conceivably an echo of the Dead Sea ... So the (South Barbarian) people make boats of

stoneware and iron when they want to cross it. (See Needham, Joseph; Note f, page

665.)

Chinese Junk in History, Art and Literature

Among the meager arts and crafts practiced by primitive man, the

knowledge of how to propel himself in or on some form of floating vessel was so certainly

acquired from the very earliest time that this fact has been taken for granted by all

ethnologists and antiquaries.

According to Chinese legendary history, all useful inventions, together

with the philosophy of the sages, were said to be mentioned in the earliest of the

classics, the " I Ching ", or " Book of Changes," and its

appendices. The art of boatbuilding is also claimed by some (although this is difficult

to believe) to be represented in the system of symbols of which the "I Ching"

consists. One of these appendices, written after the time of Confucius, describes how

Fu Hsi, the first of the five great rulers, traditionally dated 2852 B.C., taught the

people many useful arts, including that of fishing with nets and how to make the first

boats. These were built by "hewing planks and shaping and planing wood."

Tradition makes a lot of Fu Hsi, who was credited with being the

offspring of a nymph and a rainbow. One of the most outstanding of the legends describes

how celestial aid was sent him in his efforts for the enlightenment of his people by the

sudden appearance of a " dragon " horse bearing a scroll on which were inscribed

the eight mystic trigrams known as the pa-kua, which play so important a part in

Chinese divination and philosophy. Little more is told us of this interesting personality

except that he "dwelt in a hall, wore robes, introduced rafts and carts,"

and fittingly terminated his picturesque career by ascending to heaven on a dragon's back.

(The Junks & Sampans of the Yangtze, G. R. G. Worcester, US Naval Institute Press,

Annapolis, Maryland 1971, pp. 7.)

More or less authentic descriptions and paintings, dating back to 2600

B.C., exist of the ships of ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, and even of India and Persia.

That is to say, the data available can be safely assumed to be so tolerably accurate in

general that these ships can be reasonably reconstructed, and many old pictures of them

are to be found which would not offend the historian or the sailor; but there is

nothing of the kind relating to ancient Chinese junks'. No chapter in the history of

China is so incomplete - as that concerning ships and sailors. There is no general

collection of pictures, nor can literary sources be regarded as satisfactory. (The Junks

& Sampans of the Yangtze, G. R. G. Worcester, US Naval Institute Press, Annapolis,

Maryland 1971, pp. 9.)

The Shang people lived by agriculture, herding flocks and cattle, and

by hunting. They were by no means a nautical people.

Excavations carried out at Anyang show that the Shang people buried

with their dead a great variety of objects, some of exquisite workmanship. Moreover, their

royal tombs were most elaborately constructed and decorated. It is infinitely to be

regretted that nothing nautical, apparently, has come down to us. The inclusion of

but one model boat would have been of inestimable assistance to nautical research. So

cultured were these people, unlike some of the dynasties which followed them, that great

reliance could have been placed on any contribution they made.

The Shangs were conquered by the Chous, who founded the dynasty of that

name. At first they were vastly inferior in their culture and quite unimportant from a

nautical point of view except that they produced that great man the Duke Chou, who is

credited by some with the invention of the compass, and this dynasty provided much

literary material, notably the "I Ching", or " Book of Changes "; the

" Shang Shu ", or "'Book of History "; the "Shih Ching", or

"Book of Poetry," and others which will be referred to later.

Interesting as all this may be, it casts no real light on the

subject of nautical research in China. In default, therefore, of any reliable records

of Chinese craft, the would-be historian, in trying to trace their evolution, is naturally

led to make researches into the craft of contemporary or more ancient civilizations in

that cradle of all civilizations, the Near East, and then to endeavor to link up with, or

in some way explain, the Chinese types. The more this method is pursued, the more

similarities come to light, so that it would seem that so many licenses could not be due

to mere coincidence. Yet, unhappily, the exact opposite is equally easy to prove.

In seeking to trace the origins of the various types of craft it is

natural to study not only the sculpture, literature, drawing, and painting of a country,

but also its ceramic art, together with coins and seals, which have all, in the West,

proved such a fruitful field for nautical research.

Very little can be gleaned from the earliest known representations

of Chinese craft. Probably the oldest are three sampans on a sculptured slab of stone

from a rock tomb of the Later Han dynasty, A.D. 25-221, situated fairly close to the tomb

of Confucius at Hsiao T'ang Shan. These are depicted as assisting in the operation

entitled " the Urn of Chou being brought out of the river." The seated occupants

of the boats use a paddle, while in one boat a man stands with a pole, which he may be

using either as a quant or as a sounding-pole.

Probably the second oldest portrayal of sampans is similarly sculptured

on the walls of a stone tomb of a family named Wu, at Tzủ Yủn Shan, also in Shantung,

dated about A.D. 147. These craft are heavier in type and have a more characteristic

shape. The method of propulsion seems to be more in the nature of an oar than a paddle and

is still operated from the stern.

As sculptors in stone the Chinese have produced very little else

that is of interest to the nautically-minded. It is notable that in their stone or

earthenware tomb figures and articles junks play no part at all. Except for those

described above and the much-quoted fresco at Ajunta, in India, to be described later,

which, even if it represents a- Chinese junk, was probably not executed by a Chinese

artist, there are no other murals of note showing junks, and the only examples of junks

carved in stone are the fanciful jade or soapstone objets d'art from the curio shops or,

last and worst of all, the Dowager Empress's marble boat in the Summer Palace in Peking.

This stone atrocity of dreadful design was built from funds which had been ear-marked for

the navy.

As regards drawing and painting, junks and sampans frequently appear as

motifs in early Chinese paintings of all dynasties after the Han dynasty, of which no

authentic drawing or painting has come down to us. Some of the early representations

clearly incorporate many features and fittings still in use to-day; but these are

accidents reflecting more credit on the artist's powers of observation than his knowledge

of rigging and seamanship. It is noteworthy that the Chinese artists confine themselves to

painting the craft of river and lake, never do they attempt the sea-going type of junk. They

never drew a boat for the sake of the boat, but only as an accessory because a sage,

philosopher, or high official happened to be meditating in the vicinity.

Landscapes, in particular those depicting mountains and streams, rank

highest in Chinese paintings, after which come studies of birds and flowers, dragons, and

mythical creatures and animals. Chinese art is so stylistic that everything is cast in a

stereotype mould. The rules require that any large sheet of water portrayed should be

studded with sails, and a recognized technique was developed. (The Junks & Sampans of

the Yangtze, G. R. G. Worcester, US Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland 1971, pp.

14.)

It is difficult to arrive at any conclusion from many of these drawings

owing to the obviously inadequate knowledge some of the artists had of the craft they

illustrated. The Chinese practice of repeating famous pictures, with variations

sometimes, and their habit of copying earlier masters is a great help to the student of

the periods and styles of ancient artists but it is unfortunately no help to nautical

research. In the study of Chinese art due allowance must always be made for the

conventionality of the drawing, and this applies with equal force in the matter of Chinese

junks.

In Chinese literature there is much more material upon which to draw,

although the allusions are not very specific or instructive. There are always references

to junks and sampans in the classics and the old dictionaries. Vague mention is made to

the tribute brought by various tribes to the Emperor Yủ, which are described as

"floating along down the rivers Huai, Ssủ, and Huang ." The semi-barbarous

kingdom of Yủeh, comprising what is now Chekiang, about 472 B.C. had the largest navy of

any of the feudal states and fought always on water, never using war chariots. There was a

21-years' war between this tribe and the state of Wu. The state of Yủeh became a maritime

power, and it is probable that, when it is said that the Chinese reached the Yangtze cape

in 1200 B.C., this was the occasion of the foundation of this maritime tribe.

Although the date of 1200 B.C. has been asserted with some confidence

as being the time that the sea coast in the vicinity of the Yangtze was first reached, it

seems far more probable that the Chinese had started their maritime adventures at a very

much earlier date, although their excursions would have doubtless been at first confined

to fishing, fighting, and other purely local activities.

Sea fights are specifically mentioned as early as 473 B.C., and it is

stated in the "Shih Chi", the first general history of China, dating back to

about 90 B.C., that:

The King of the Wu kingdom made an attack upon the Ch'i kingdom from

the sea, but was defeated and turned home.

Two years later, in a contest between these two marine kingdoms, the

ruler of the Yủeh ordered his general to proceed along the coast and carry out an attack

up the Huai River, which at that time entered the sea by its own estuary.

Among the many voluminous Chinese dictionaries, there is the " Shuo Wen by Hsu

Shen, who died in A.D. 120. It comprises some 10,000 characters, but, despite numerous

references to ships, there is nothing really descriptive of any craft that can be used as

evidence of the existence of any definite type at any particular time.

In respect of one of the earliest mentioned voyages to the East,

researches into the "Book of History " and the " Book of Odes " reveal

how it is recorded that in 219 B.C. the Emperor Shih Huang, of the Ch'in dynasty, ordered

Hsu Shih to go on an expedition with "several tens of thousands of youths and maidens

to search for the three fairy Isles of the Blest." Other authorities have described

how they started off from Shantung, and it is confirmed by various sources that they

actually reached Japan. Unhappily, history does not appear to relate what success

attended their mission. (The Junks & Sampans of the Yangtze, G. R. G. Worcester,

US Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland 1971, pp. 16.)

In Europe, coins and, later, seals form a useful source of our

knowledge of the craft of the ancients. From seals especially the evolution of the sailing

ship can be followed. By their aid the development of the rudder, the growth of the

forecastle and poop, rigging, the bowsprit, and even fenders can be accurately traced and,

which is so important, dated. Unhappily there is nothing of the kind in China.

The Ku Pu spade coins, so called on account of their shape, are said to

originate from the middle of the Chou dynasty, 1122-255 B.C., but it was not until some

2,000 years later, in 1931 to be exact, that anything nautical made its appearance.

This was on the Sun Yat Sen 1 yuan. The very fine representation of a junk thereon is said

to typify the ship of state, with Sun Yat Sen's Three Principles depicted by the three

birds overhead, the Kuo-min-tang, being the sun's rays. This was issued at a time when

Japan took the Three Eastern Provinces. The issue was recalled and the dies changed as it

was thought that the three birds were the three provinces flying away from China under the

influence of the sun rays of Japan. This coin is now very valuable and is extremely

artistic. (The Junks & Sampans of the Yangtze, G. R. G. Worcester, US Naval Institute

Press, Annapolis, Maryland 1971, pp. 14.)

Finally, Worcestor went to an conclusion like this: "And so we

leave our researches with a final regret that Chinese painting, literature, and culture in

all its many forms and with its amazing and continuous tradition of 2,000 years should

contain so little about her ships and sailors."

Acquisition by Discovery ?

"Discover" is defined in "Webster's Dictionary" as

:

1. to be the first to find out, see, or know about.

2. to find out; learn of the existence of, realize.

3. (a) to reveal; disclose; expose; (b) to uncover. [Archaic.)

Syn.- invent, manifest, declare, disclose, reveal, divulge, uncover.

China claims: China discovered the Nansha and Xisha Islands over 2,100

years ago, during the Han Dynasty. The discoverers, Admiral Yang Pu and his subordinates,

were sent by the Emperor of the Han Dynasty".

People realized that the Chinese has just known Southeast Asia,

especially Bien Dong very late, supposedly 2,100 years ago. Long time before, as least

4,000 years ago, the local people Southeast Asian, including Vietnamese had adventure to

go out the Sea to reach the most remote shores of Siberia, India, Africa…. In more

ancient time, the first "Boat People" of Bien Dong certainly reached Australia

after long raft journey. Such 60,000 years old expeditions for sea discoveries was already

certified by Scientists.

According to international law and custom at the time, "who

discovers the territory, holds its sovereignty." Since Southeast Asians, the

local inhabitants; clearly maritime oriented, discovered the Nansha and Xisha Islands;

Chinese, originally land people from a far away country, can not hold the sovereignty over

these islands.

Before the eighteenth century, discovery and symbolic occupation were

enough for a claim of sovereignty, and China's claim of sovereignty over Truong-Sa and

Hoang-Sa (Chinese Nansha and Xisha Islands) could have been sufficient to be recognized as

valid. However, since the eighteenth century, claims of sovereignty by discovery need to

be followed by effective occupation and acts of authority. All these facts was never

qualified for the Chinese verifications.

Because there was not Vietnamese writing 2,100 year ago, the Chinese

Han history books must be considered as the best evidence and we invite a joint study.

Even the best investigation can not reveal any clues about Paracels/ Spratleys

discovering. No any trace relating the "knowing" or "seeing" was

mentioned in there!

After reading Han Shu, Vietnamese or anybody else believed that Chinese

Admirals as Yang Pu or Ma Yuen, in most of their war-times, walked. Yang Pu walked to

P'an-yu (the modern city of Canton) then stopped there. Ma Yuen marched with his armies

thousand miles more. Both of them seldom rode Nam-phuong Lau-thuyen (Viet's boats)

hundred miles the most, they did not go South very far, and nothing in History can prove

that they went offshore!

It is necessary to give a short comment here. These were the first two

Chinese wars invading the South (Nan Yủeh then, Viet Nam now), Commanding Generals

betitled Admirals but Chinese Admirals had no Chinese-build ship. All their vessels were

"nan fang lou hsiang" -nam phuong lau thuyen in Vietnamese. Nan fang was, at

that time, named for the People of State in the South, Nan Man or Nan Yủeh People. The

ship crew may be South People too! Chinese could build ship but in much later time...

The cases of Paracel and Spratly Archipelagoes

Chinese officials, long preoccupied with their continental empire and

more specifically with the northwest, had an equally vague sense of the sea as a separate

world in its own right, different from the land in its movements, rhythms, and

dynamics. Although they implicitly recognized the zones of the water world—coastal

strip, inshore waters (nan-hai), and creep sea (nan-yang)—they diet not conceive of

them as an integrated whole.

It is not surprising, then, that the vocabulary they used to describe

their maritime environment is at best imprecise and unclear. Whereas in the West the terms

sea and ocean are roughly differentiated to the extent that a sea is thought of as being

bounded in some way, for the Chinese hai (sea) and yang (ocean) were completely

interchangeable." Although a few cartographers did make a vague distinction between

hai as the shallow waters lying immediately off the coast and yang as the deep waters

farther out, it is impossible to find a Chinese map showing where one gave way to the

other. Most Chinese maps label all expanses of water as one or the other. The only

important distinction for the Chinese was between the "inner" (net) sea or ocean

and the "outer" (wai) sea or oceans. In the study of Dian H. Murray (1987), the

waters referred to as the ''inshore seas of the Nan-hai'' usually appear on Chinese maps

as either nei-hai or nei-yang; and those referred to as the "deep seas of the

Nan-yang" usually appear as wai-hai or wai-yang.

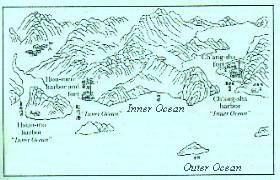

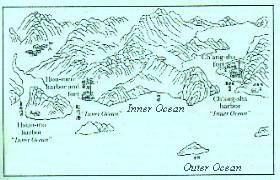

Map shows the "inner" and " outer" oceans off

Kwangtung province's south coast. Note how close to land the Chinese of the day thought

the outer (largely unknown) ocean lay. Officials tended to perceive the "inner"

ocean as the farthest extent of their authority. From Kuang-tung hai-fang hui-lan, Comp.

Lu K'un and Ch'eng Hung-ch'ih, n.d.. Vol.

Although the (above) Map has no scale. it shows where Chinese

cartographers and officials believed the outer- ocean lay. Places no farther from shore

than the Ladrone Islands at the mouth of the Pearl River were placed in the- wai-yang. For

all practice purposes, that is to say, the outer- ocean began just beyond where the eye

could see. In effect this meant that all outlying areas were virtually unknown.

They were also of little concern (about offshore lands). For example,

although the Chinese made sweeping claims to the Spratly and Paracel islands, they made

little attempt to incorporate them into their empires As late as the nineteenth century

cartographers still disagreed about their exact location, and Confucian literati regarded

them as little more than "a series of navigation hazards [at] the eastern edge of

China's maritime gateway."

Accordingly, the narrow zone of the inner sea marked the farthest

seaward extent of active Chinese governance. In choosing not to make coastal control a

high priority, Chinese officials forfeited the opportunity to seize the military

initiative in maritime China. As a result, theirs was a weak and passive presence in the

heart of the water world. (See more arguments in Pirates of the South China Coast

1790-1810, Dian H. Murray, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 1987.)

Conclusion: Chinese are Landmand and Perfect Strangers of the Easter Sea

The "have boat, will travel" argument, of course may not

enough to convince China, but people also have many more critical arguments about the

Chinese anti-maritime nature. So, this paperwork is long enough to go to the firm

conclusion :

"Chinese are Purely Land Men and Perfect Strangers in the Eastern

Sea".

Vu Huu San

South China Sea dispute: The

inconvenient truth that Han Chinese sailors are latecomers

in history

The

conflict between the Philippines and China over the

Scarborough Shoal may appear

at first sight a minor dispute over an uninhabitable

rock and surrounding shallow

waters. But

it is hugely important because it encapsulates China’s

assumption that the histories of the non-Han peoples

whose lands border two-thirds of the waters known in

English as the

South China Sea

are irrelevant.

Malays are the greatest sailors of the ancient world

The Philippine case over

Scarborough has been mostly presented as one of

geography. The feature is 135 nautical miles from Luzon,

the main Philippine island, and roughly 350 miles from

the mainland of China and 300 miles from the tip of

Taiwan. It is thus also well within the Philippines’

Exclusive Economic Zone.

China leapfrogs these

inconvenient

geographical truths to come up with

justifications of its claims which can be applied to the

whole South China Sea and thus

justify the

dotted line on map

which vaguely defines them.

This line has never

been precisely delineated but comes well within the

200-mile limits of all the other countries, and close to

Indonesia’s gas-rich Natuna islands.

In the case of the

Scarborough Shoal,

its historical justification is that this rock and

surrounding shallow

water is mentioned in a Chinese map of the 13th

century when China itself was under alien – Mongol –

rule. The fact that a vessel from China had

visited the shoal and recorded its existence has thus

become one basis for its claim. Very similar pieces of

history are trotted out to justify claims to other

islands visited by ships from China. Likewise,

China’s assumption of hegemony is often based on the

fact that foreign merchant ships had to pay taxes to

trade with China.

History, however, shows

that

Chinese sailors were latecomers to the South China Sea,

let alone to onward trade to the Indian Ocean.

The seagoing

history of the region, at least for the first millennium

of the current era, was dominated by the

ancestors of

today’s Indonesians, Malays, Filipinos and (less

directly) Vietnamese. Thus, as China’s own

records reveal,

when the 4th century Buddhist

pilgrim Fa Hsien, went to Sri Lanka, he travelled

from China to Sumatra and then on to Sri Lanka in Malay

ships.

This was not the least

surprising given that during this era of sea-going

prowess, people from

Indonesia were the

first colonisers of the world’s third largest island,

Madagascar, some 4,000 miles away. (The

Madagascan language and 50% of its human gene

pool are of Malay

origin.) This was a thousand years before the

much-vaunted voyages of Chinese admiral Zheng He in the

15th century.

Malay seagoing prowess

was to be overtaken by south Indians and Arabs, but they

remained the premier sea-farers in

Southeast Asia until well into the era of European

dominance of the region.

Indeed, the

Malay-speaking Hindu (like much of Southeast Asia at

that time) mercantile state of central

Vietnam

dominated South China Sea trade until the 15th century.

The 10th century

Arab traveller and geographer al-Masudi made

reference to the

“Cham Sea”, and trade between Champa and Luzon was well

established long before the Chinese drew their 13th

century map. As Scarborough Shoal not only lies

close to the Luzon coast but is on the direct route from

Manila bay to the ancient Cham ports of Hoi An and Qui

Nhon, it was known to the Malay sailors long ago.

All in all, the Chinese

claim to have ‘been there first’ is like arguing that

Europeans got to Australia before its aboriginal

inhabitants. But given China’s reluctance to acknowledge

that Taiwan was

Malay territory until the arrival of European

conquerors, and then of a surge of settlers from

the mainland, such refusal to acknowledge the rights of

other peoples is not surprising.

At times, China itself

seems to recognise the flimsy basis of some of its

historical claims. In the case of the Scarborough Shoal,

it backs up its position by reference to the Treaty of

Paris 1898 concluding the Spanish-American war and

yielding Spanish sovereignty over the Philippine

archipelago to the US. This did not mention the shoal

but described a series of straight lines drawn on the

map which left the shoal a few miles outside the 116E

longitude defined by the treaty.

Given that China rejects

“unequal treaties” imposed by western colonialists, it

is remarkable to find it relying on one between two

foreign powers conducted without any reference to the

inhabitants of the Philippines. Vietnam can equally well

claim all the Spratly Islands as inheritor of French

claims over them.

For sure, China has the

power to impose its will. But

its aggressive

stance towards the Philippines, so often seen as

an especially weak state, has alerted others, including

Japan, Russia and India as well as the US,

to its long-term

goal which is not ownership of a few rocks but strategic

control of the whole sea, a vital waterway

between northeast Asia and the

Indian Ocean, the Gulf and Europe. The Scarborough

Shoal is not just a petty dispute over some rocks.

It is a wake-up call for many countries.

Philip

Bowring is former editor of the Far Eastern

Economic Review.

|